DETROIT – The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issued its winter outlook for the three month period from December to February today.

I participated in a national teleconference call this morning with Mike Halpert, Deputy Director of NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, and then spoke privately with him this afternoon.

Recommended Videos

NOAA’s official national precipitation forecast for this winter includes a bullseye signifying a forty percent chance of wetter than average conditions over the Great Lakes. I asked Mike what in the data pointed toward this, and he told me that one of their dynamical models triggered that bullseye largely based upon a weak La Niña developing in the Pacific Ocean.

A La Niña occurs when cooler Pacific surface waters push eastward toward the western part of South America, and the warmer waters push west toward Indonesia. There is a tremendous interaction between the oceans and the atmosphere, and that why the El Nino / La Niña patterns you here us talk about so often impact the jet stream configuration which, in turn, impacts our weather pattern.

Normally in a La Niña winter, that precipitation bullseye is a little farther south, so seeing it right over us certainly caught my attention. The big “if” in this winter’s forecast largely hinges on if that La Niña continues developing.

Mike mentioned that, if the La Niña weakens and Pacific conditions return to a neutral state, then the winter outlook will have to be re-evaluated next month. But right now the expectation is that we’ll have a weak La Niña, and this is the primary driver for the outlook.

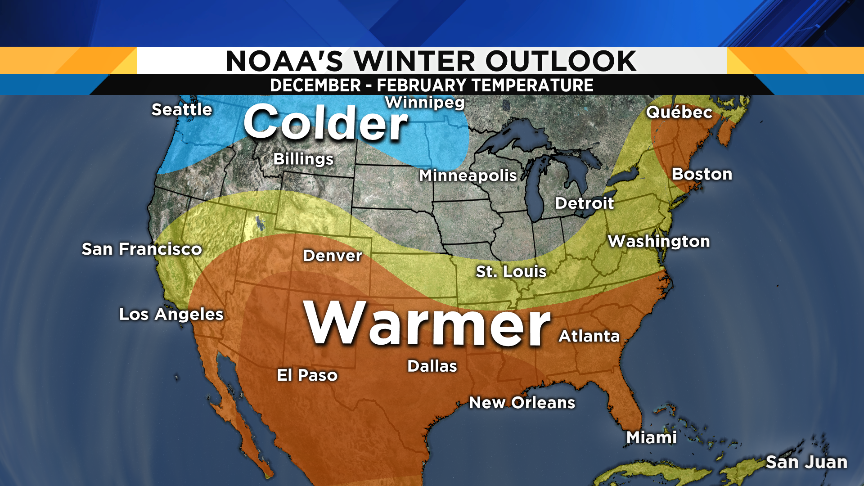

Notice in NOAA’s winter temperature outlook that we are in-between the above and below average areas. Technically, that area is called “Equal Chances,” and it doesn’t necessarily mean that we’ll have “average” temperatures.

Rather, Equal Chances means that the models did not provide a strong enough signal to say if that area will be above or below average. We are, however, much closer to the warmer than average area than the colder than average area.

So, does that mean anything for us? Well, give the higher probability for a wetter than average winter, that could mean a slightly better chance for ice and rain, instead of snow. But Mike emphasizes that these outlooks are the average for the ninety day period from December through February, and do not represent individual big storms.

For example, we could get pounded with storms over a three week period, with the remaining nine weeks being relatively quiet. So the three-month total precipitation in this example could be above average, even though three-quarters of the period had relatively light or “normal” precipitation.

There is one other thing I discussed with Mike: some of the other circulation patterns with possible seasonal impacts that I track, such as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), the Arctic Oscillation (AO), the Antarctic Oscillation (AAO), the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), and the Pacific - North America Pattern (PNA).

Mike said that, on a seasonal scale, these patterns’ impact are much less known. El Nino / La Niña remains the primary driver of our winter season, and the implications of phase combinations of those other circulations still need to be determined.

I greatly appreciate Mike Halpert’s time today. It was a privilege to have the chance to speak with him, and I should also add that he did his graduate work in meteorology at The University of Michigan! He and I overlapped one year there!